Lab Members

Current and former lab members are all here.

Find out how to join the team here

Congratulations to all involved in this multi-disciplinary exploration of the molecular determinants of K2P channel selectivity.

Congratulations to all involved in this multi-disciplinary exploration of the molecular determinants of K2P channel selectivity.

Potassium channels play a central role in modulating cellular excitability, particularly of neuronal cells. Their unique structure determines their ability to let ions pass selectively through cell membranes. The impact of pathological or evolutionary variations in this selectivity filter remains difficult to predict. Here, we reveal that UNC-58, a member of the two-pore domain potassium (K2P) channel family of C. elegans, exhibits an unusual sodium permeability due to a unique cysteine residue in its selectivity filter. Our findings underscore the importance of functional studies to determine how sequence variation in potassium channel selectivity filters can shape the electrical profiles of excitable cells.

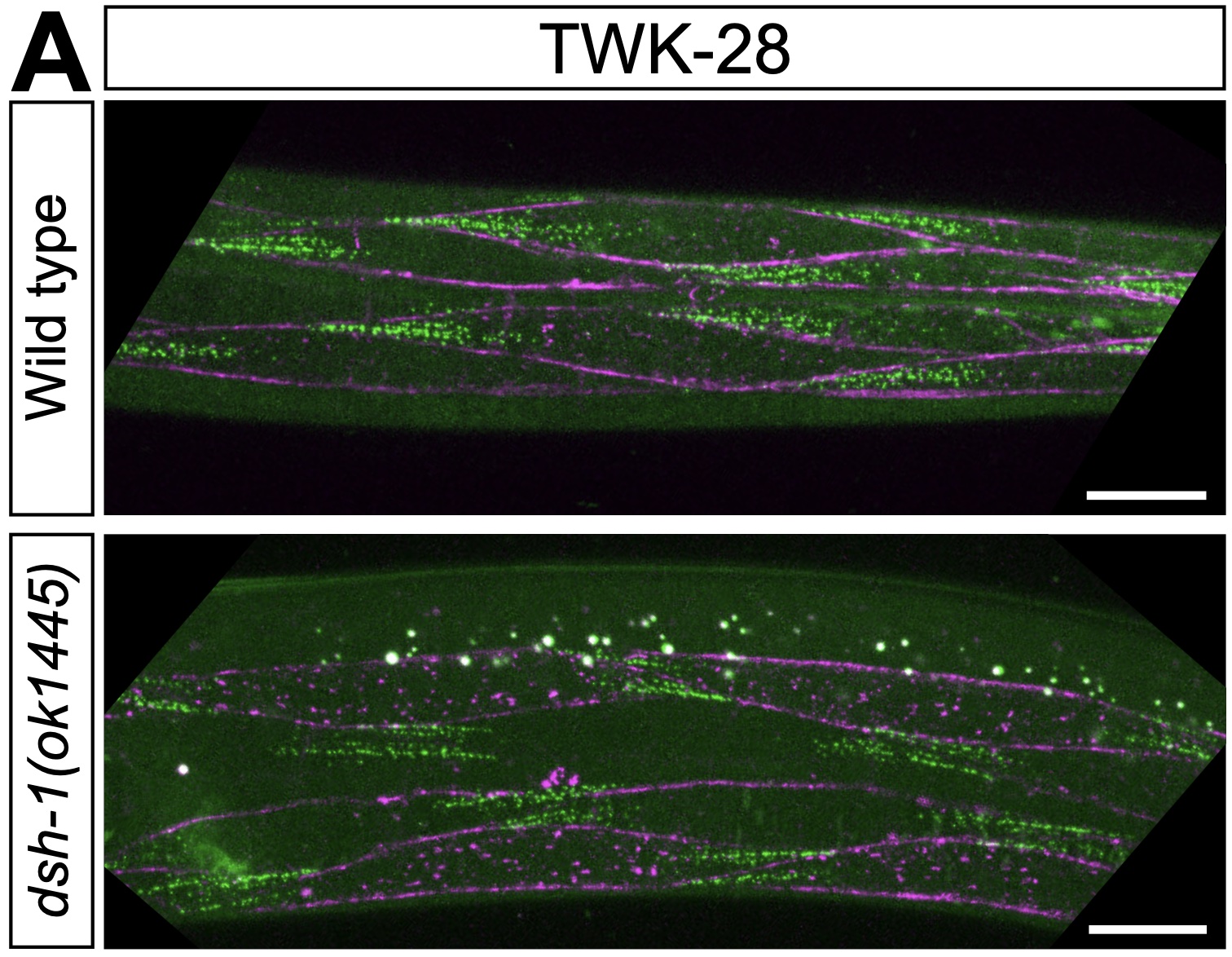

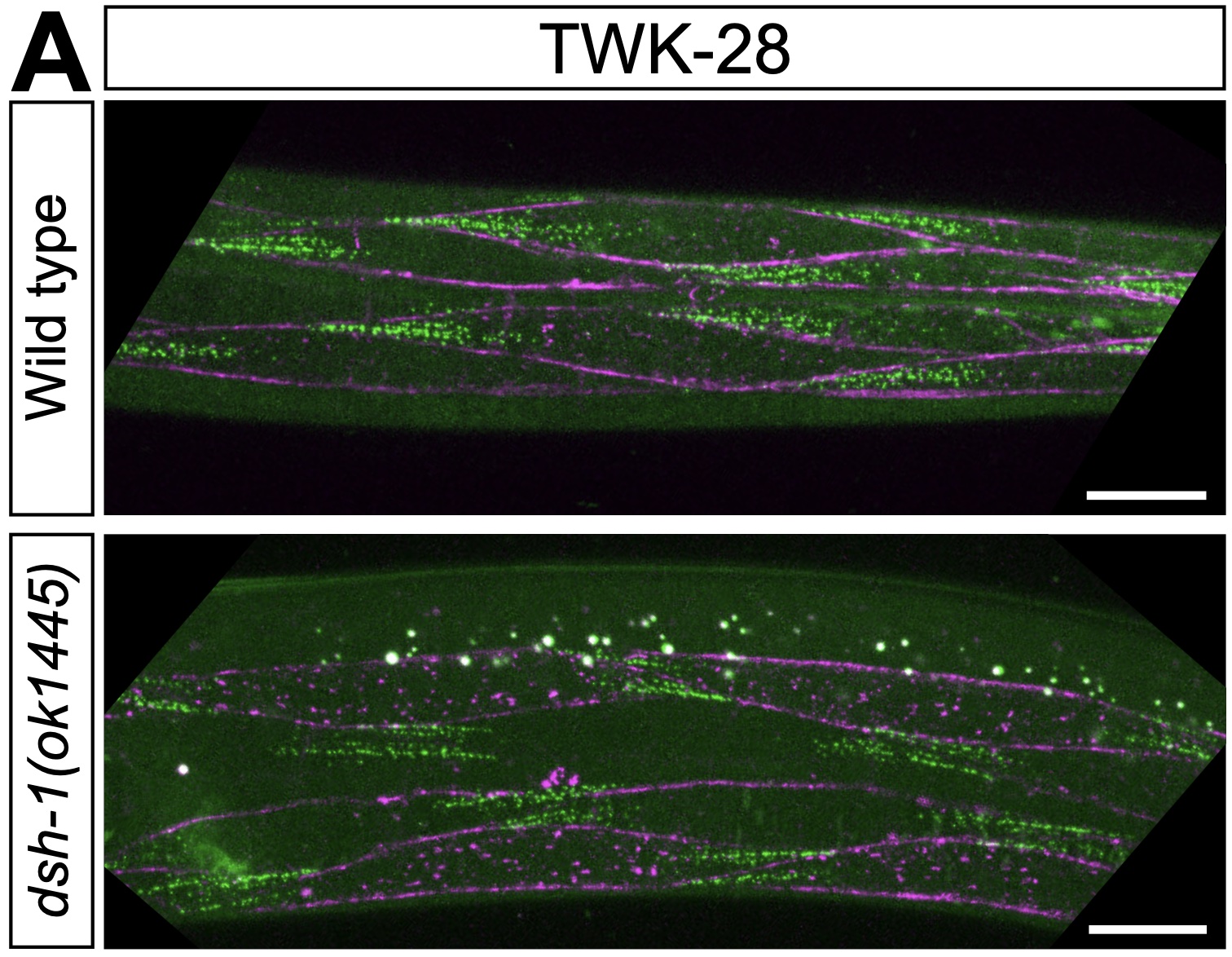

Our study revealing the remarkably complex organisation of the worm's sarcolemma is now out at Nature Communications!

Our study revealing the remarkably complex organisation of the worm's sarcolemma is now out at Nature Communications!  Congratulations to Jun, Sonia El Mouridi, and the teams of Mei Zhen and Shangbang Gao for our first collaborative study about the exquisite regulation of C. elegans locomotion.

Congratulations to Jun, Sonia El Mouridi, and the teams of Mei Zhen and Shangbang Gao for our first collaborative study about the exquisite regulation of C. elegans locomotion.

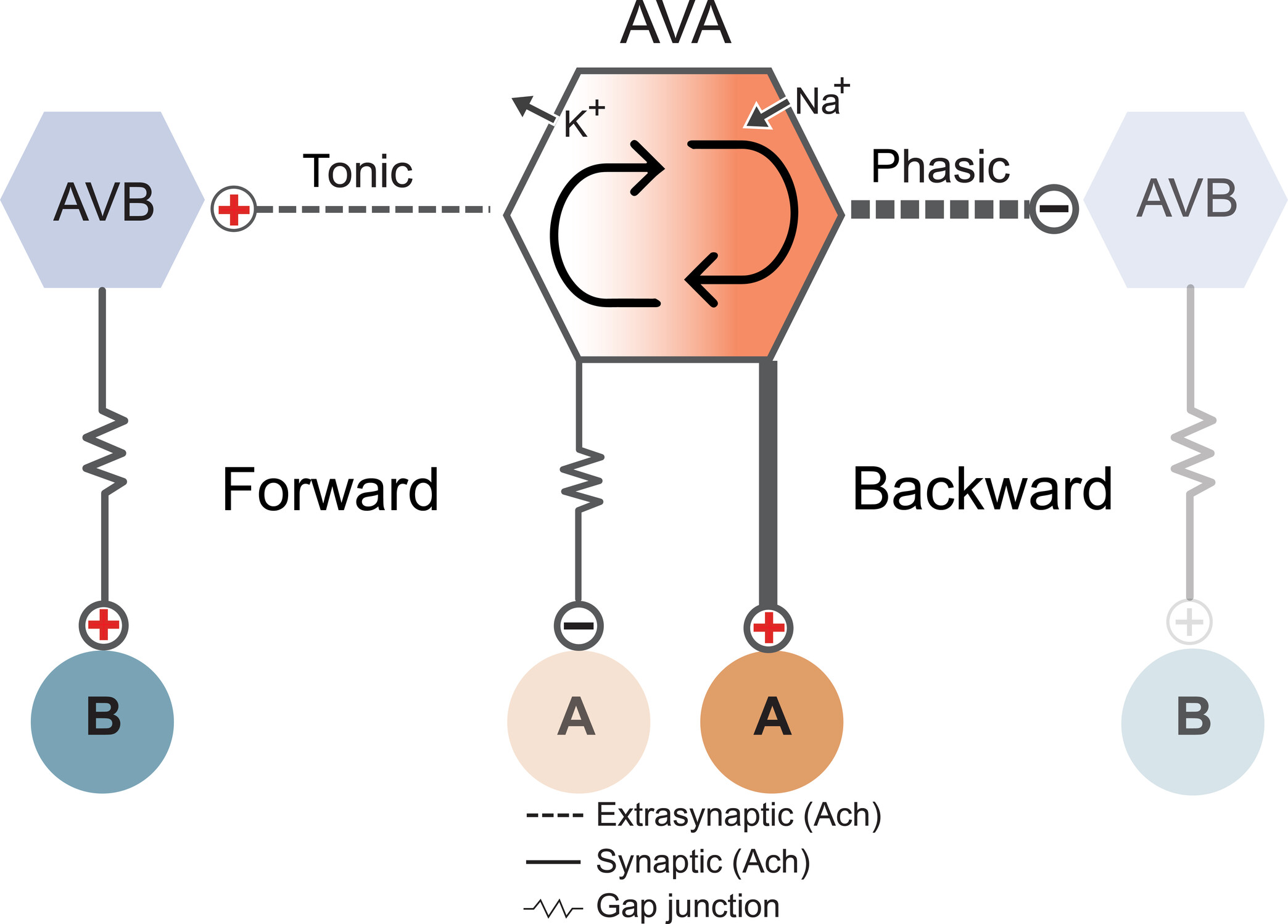

In this study, we report a new conceptual framework for a universal problem in motor control: how do animals generate smooth transitions when switching between opposing motor states like forward and backward locomotion? We analyzed circuits for forward and backward locomotion in C. elegans with single cell endogenous membrane potential perturbations, electrophysiology, calcium imaging, and mathematical modeling. In contrast to the prevailing view, our results establish a new model for smooth and continuous behavioral transitions between forward and backward locomotion.

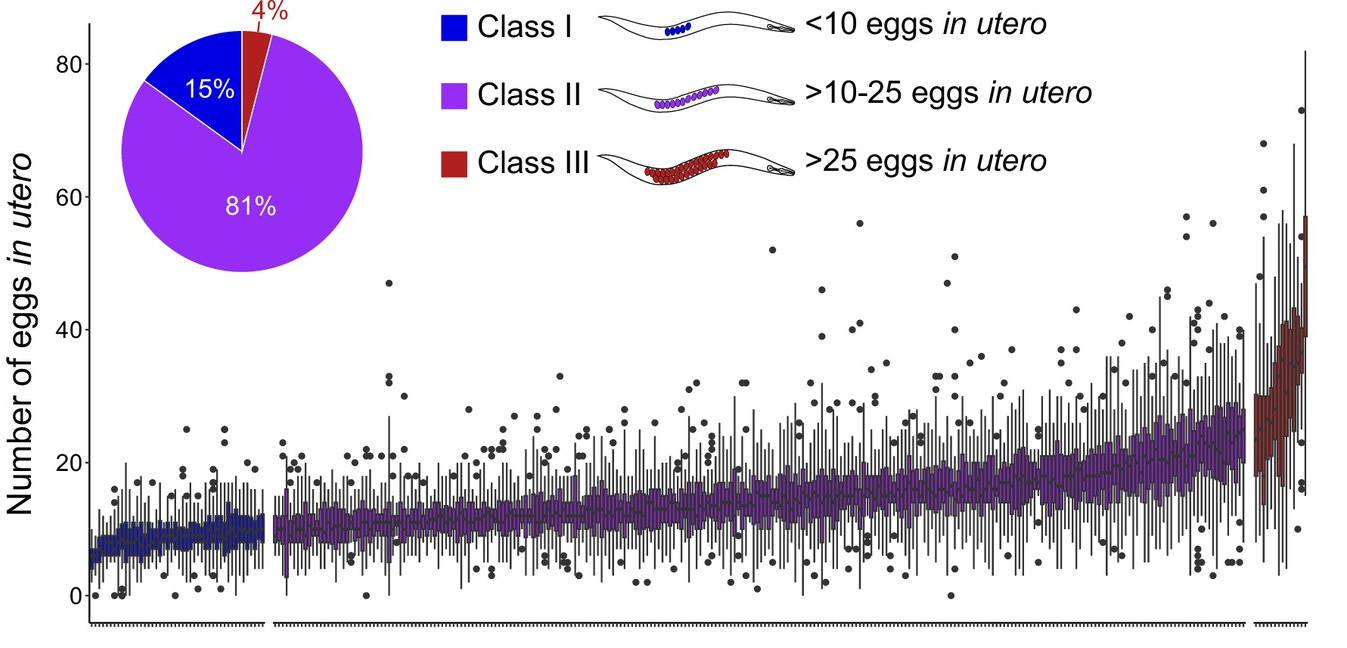

Congratulations to Laure Mignerot and the team of Christian Braendle for our second collaborative study about the natural variation of the C. elegans egg-laying behaviour.

Congratulations to Laure Mignerot and the team of Christian Braendle for our second collaborative study about the natural variation of the C. elegans egg-laying behaviour.

eLife assessment - This important work provides a thorough and detailed analysis of natural variation in C. elegans egg-laying behavior. The authors present convincing evidence to support their hypothesis that variations in egg-laying behavior are influenced by trade-offs between maternal and offspring fitness. This study establishes a framework for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying this paradigm of behavioral evolution.

Within the framework of the NERVSPAN European Doctoral Training Network, we are offering a fully-funded PhD fellowship to study the robustness of neuronal excitability and function across gender and lifespan.

The intrinsic electrical properties of neurons are defined by the repertoire of ion channels they express. Determining the precise genetic programs that establish the electrical identity of neurons remains a major question in cellular neuroscience. Single-cell transcriptomic studies in the C. elegans nervous system have revealed that potassium channels are often expressed in complex combinations of over a dozen channel genes in a single neuron. These different ion channel combinations will determine the biophysical and electrical properties defining neuron-specific functions throughout its life.

From a conceptual point of view, this project will address for the first time how ion channel degeneracy, variability and covariation are genetically regulated to ensure the resilience and phenotypic stability/plasticity of excitable cells in C. elegans.

NERVSPAN will train 12 doctoral Students at 7 academic institutions and 1 company. The nature of the programme will provide the enrolled students with strong interdisciplinary training (including, but not limited to: molecular biology, bioinformatics, high resolution microscopy, proteomics, and transcriptome profiling).

Congratulations to Antoine, Olga and the team of Philippe Chevalier (Rhythmology department, HCL Lyon) for our first collaborative study about Kv11.1/hERG potassium channels.

Congratulations to Antoine, Olga and the team of Philippe Chevalier (Rhythmology department, HCL Lyon) for our first collaborative study about Kv11.1/hERG potassium channels.

Our project with the team of Vincent Mirouse (iGred, Clermont-Ferrand) and Helge Amthor (UVSQ) has been selected by ANR ! The Dystrophin Associated Protein Complex (DAPC) is a key actor of the cell – extracellular matrix (ECM) interface, as revealed by its implication in human genetic disorders. However, its molecular and cellular functions are still poorly understood because tractable model systems allowing state-of-the-art in vivo cell biology and genetic approaches are lacking. Our three teams have developed the first transgenic dystrophin reporters that have revealed remarkably compartmentalized membrane distributions of the DAPC in epithelia and muscle cells in C. elegans, Drosophila, and mouse. The project aims to elucidate the organization and dynamics of the DAPC and to characterize its new functions in relation to specific cell cortical compartments.

Our project with the team of Vincent Mirouse (iGred, Clermont-Ferrand) and Helge Amthor (UVSQ) has been selected by ANR ! The Dystrophin Associated Protein Complex (DAPC) is a key actor of the cell – extracellular matrix (ECM) interface, as revealed by its implication in human genetic disorders. However, its molecular and cellular functions are still poorly understood because tractable model systems allowing state-of-the-art in vivo cell biology and genetic approaches are lacking. Our three teams have developed the first transgenic dystrophin reporters that have revealed remarkably compartmentalized membrane distributions of the DAPC in epithelia and muscle cells in C. elegans, Drosophila, and mouse. The project aims to elucidate the organization and dynamics of the DAPC and to characterize its new functions in relation to specific cell cortical compartments.

Our study revealing the remarkably complex organisation of the worm's sarcolemma is now on BioRxiv!

Our study revealing the remarkably complex organisation of the worm's sarcolemma is now on BioRxiv!  Our project with the team of Christian Braendle (iBV Nice) and ViewPoint: Behavior Analysis Technologies has been selected by ANR ! On the heals of our joint publication (Vigne et al., Science Advances 2021) we will be trying to understand how specific neural circuits evolve to generate natural behavioural variation within species. In particular, the precise genetic changes that modulate cellular and developmental architectures of reproductive systems remain unclear. Here we will focus on the simple egg-laying circuit of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a powerful model system to study natural microevolutionary (intraspecific) variability.

Our project with the team of Christian Braendle (iBV Nice) and ViewPoint: Behavior Analysis Technologies has been selected by ANR ! On the heals of our joint publication (Vigne et al., Science Advances 2021) we will be trying to understand how specific neural circuits evolve to generate natural behavioural variation within species. In particular, the precise genetic changes that modulate cellular and developmental architectures of reproductive systems remain unclear. Here we will focus on the simple egg-laying circuit of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a powerful model system to study natural microevolutionary (intraspecific) variability.

Current and former lab members are all here.

Find out how to join the team here

Find out here about our current projects.

Find out here about our (past) science.

None of this works without it.

Coming to the lab.

About what is going on in the lab.